What you need to know about Ohio Politics and Policy

Ohio Resistance Guide

The Ohio Resistance Guide is brought to you by fellow resisters who have worked at the Ohio Statehouse in both the legislative and executive branches. We want to share what we know so that you can make your voice heard just as loudly in Columbus as you are in D.C.

Table of Contents

FROM THE INDIVISIBLE TEAM

WHY STATE GOVERNMENT MATTERS

CHAPTER 1: KEY DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CONGRESS AND THE STATEHOUSE

CHAPTER 2: HOW CAN YOU HAVE INFLUENCE?

CHAPTER 3: WHAT GOES ON AT THE STATEHOUSE

CHAPTER 4: WORKING WITH THE EXECUTIVE BRANCH

CHAPTER 5: LEARN MORE ABOUT LEGISLATION

ONLINE RESOURCES

From the Indivisible Team

Dear Reader,

When we put the Indivisible Guide online as a poorly formatted, typo-filled Google Doc, we never imagined how far and fast it would spread. But across the country, individuals and groups have united to stand indivisible and hold Congress accountable.

Thanks to their hard work, we’re seeing every day what is possible when an informed, mobilized constituency demands that their voices be heard. And this approach should be applied to every layer of our democracy.

When we set out to write the guide, we wanted to share our knowledge as former staffers to demystify Congress. We’re absolutely floored that it has sparked similar efforts to explain state legislatures and local governments. There are many ways beyond congressional advocacy to contribute to the resistance, and we believe that progressive values should be defended at the local and state level as well.

Innovation’s Ohio’s tremendous resource puts the spotlight on Ohio’s state legislature and executive branch. Featuring some great tactical recommendations and handy explainers, this guide will help demystify Ohio’s government and help you hold your state elected officials accountable.

Indivisible groups across Ohio have done amazing work in the early months of the Trump administration to protect our values, our neighbors, and our democracy. Together, we have the power to resist — and we have the power to win.

We are excited to see what you do next.

Sincerely,

Ezra Levin, Executive Director, INDIVISIBLE

Leah Greenberg, Chief Strategy Officer, INDIVISIBLE

Why State Government Matters

If you care about your local schools or the cost of college tuition, state government should matter to you. If you want to live in a more safe and vibrant community, state government should matter to you. If you care about healthcare, civil rights, justice and fair elections, state government should matter to you.

Spending over $70 billion each year, state government impacts many things in our daily lives. The three biggest expenditures in the state budget are Medicaid, education, and our prison system. The state also spends billions on Ohio’s transportation infrastructure.

While we must keep fighting the Trump agenda, lawmakers at the Statehouse have the power to pass legislation right here at home. Just since the election, we have seen bills advance to block wage increases, undermine women’s health and economic security, attack the rights of the LGBT community and reverse clean energy standards.

This guide will hopefully serve as a roadmap to help Ohioans better understand how state government impacts the issues they care about, but also how we can leverage our collective voices to shape policy and improve our democracy.

Chapter 1

Key differences between Congress and the Statehouse

State lawmakers — members of the Ohio House of Representatives and the Ohio Senate — are people from your community. You’ll often run into them at the grocery store or coffee shop. You may already know them as former members of city council, a local school board or as community business owners.

Working in the legislature requires lawmakers to spend a few days per week in Columbus for much of the year. However, lawmakers are regularly accessible in their home districts in a way that activists should use to their advantage. And even when legislators are in Columbus, there are unique opportunities to interact with them and their staff at the Statehouse.

MORE OPPORTUNITY FOR INTERACTION

Unlike members of Congress who spend more time out of state and have much larger districts, it’s not unusual to run into members of the Ohio legislature regularly. They attend local civic meetings, high school football games and other local events. They often hold office hours over coffee or give talks in the community on legislation and issues. Many send out monthly newsletters promoting a list of upcoming events. You should also follow your legislator on social media.

MORE RESPONSIVE TO LOCAL INFLUENCE

State legislators go to Columbus because they have to, but they don’t ever want to be accused of spending all their time in Columbus. Columbus often gets used as a derogatory word, as in: “Columbus is raising our taxes again” or “That stupid law was passed in Columbus.”

When you talk to your state legislator or their staff, after you tell them your name always tell them where you live. “Hi Representative Jones, my name is Sally Smith and I live in Greenville over on Broad Street.” A seemingly friendly greeting has the added effect of immediately putting them on notice that you’re someone who determines their fate every two or four years. If you have another connection to the legislator (maybe you go to the same church or you went to school with their sister), tell them.

But don’t say to a legislator or staff, “I pay your salary!” While true, that kind of approach is generally a non-starter and a pretty sure way to get a deaf ear going forward.

Chapter 2

How can you have influence?

Having a legislature that is in session most of the year with very little attention paid to its work is actually a huge advantage to us as constituents. Unlike Congress, it’s actually realistic to expect to interact with your state lawmakers on a fairly regular basis if you’re persistent and smart about it.

Contacting a lawmaker: What works?

The best way to reach out to your legislator really depends on your objective.

- If you’re looking to get legislation introduced or have an idea for an amendment, you want to have personal, face-to-face contact with the lawmaker or their staff.

- If you want to make a specific point about pending legislation, you should testify in committee.

- To simply register support or opposition for a bill, call the legislator’s office.

- To ask a question, send an email or leave a message and you’ll almost certainly get a response.

Below is a quick rundown of some popular forms of communication and our thoughts on their usefulness.

Though easy, these outreach methods by themselves aren’t very effective:

Postcards and traditional petitions

During a legislative session they typically lay in a pile until a staffer or intern has a chance to review and input them into a spreadsheet of some kind. That can take weeks or even longer, and not a way to have impact on fast moving legislation.

To have an impact, consider taking a stack of petitions or handwritten notes to the lawmaker’s office in person.

Mass emails – including those generated by online petitions

Staffers treat identical messages as spam, and often respond with a canned response. Anything where you simply fill in your name and a few other pieces of information with no other personalization just isn’t effective.

Using this route, rewrite the provided text to personalize your message.

Personal letters work, sometimes

A non-form letter can work sometimes. Your chances are probably 50-50 of getting a personalized letter back (as opposed to form letter). However, by the time the office gets the letter, the bill may have changed, passed to another chamber, etc. This approach would be best used to raise a new issue and start a conversation with your legislator about a bill you would like to see introduced in the future, though a face-to-face meeting would be far more effective.

CALLS WORK

If you can’t meet face to face, but want to influence a lawmaker’s vote, call. You’ll likely talk to a staffer or leave a voicemail, but your message will be heard and tracked along with other calls. If you can arrange it, having multiple constituents call a member’s office on the same issue can really make an impact.

If possible, call on a Monday or Friday between 9-4 when member offices are less busy. Tell the staffer your name, that you’re a constituent (they may ask for your address) and what you’re calling about.

Be concise and use your own words. Tell them how you’d like the member to vote, or if you want, ask how the lawmaker is planning to vote. You can ask them to consider a particular factor in their decision. And be polite. The last thing you need is for a staffer to start recognizing your phone number as “trouble” and start screening your calls. Thank the staffer at the end and, if you want a follow-up, be sure to ask for it. If you get a lawmaker’s voicemail, feel free to leave a message and ask for a call back. You’ll more than likely get one, often from the member personally.

WHEN TO EMAIL INSTEAD

If you need a lawmaker to send you a document (testimony they provided at a hearing, agendas for a committee they chair, etc.) or to answer a question about legislation they are sponsoring, those types of specifics are often better responded to via email. Or, if you’re just shy or hate phones and want to ask your lawmaker to vote a certain way, a quick email works. But make sure to include your home address.

SOCIAL MEDIA

Some of our state lawmakers are very active on Twitter and/or Facebook. Take a look at your lawmakers’ social media and if they seem to be interacting with people who reach out to them, congratulations! In that case, hit them up with a simple, non-confrontational request or question. If you’re rude or aggressive, all bets are off.

IF YOU CAN, ASK FOR A MEETING

An in-person meeting is the most effective way to get a lawmaker interested in your issue, particularly if it’s not getting any attention at the moment. You may be able to meet with a legislator in Columbus, but if you can’t make the schedules work, then getting a meeting with their staff can be equally effective.

Or, instead of a meeting in Columbus, when meetings may need to be shortened to accommodate the unpredictability of legislative sessions and hearings, try meeting with your legislator in your district. Members often announce office hours when constituents can drop in without an appointment to discuss issues. Like or follow your members’ social media pages to hear about these types of opportunities, or call their office to ask to be added to their mailing list.

At the meeting, if you have a personal story about how a law is currently not working the way it should, tell it. Bring a few other people with you, if you can. If you’re alone, indicate if you are speaking on behalf of a group or organization. Connect your issue to the lawmaker’s area of interest (if you’re not sure, visit the legislator’s page on the Ohio House or Senate website and see what they talk about in their press releases).

Expect to get 15 to 20 minutes of their time, but make sure you can make your pitch in less than five if you have to. Before you go, make a specific, actionable request. It could be for a new bill to be introduced, for an amendment to an existing bill or simply to ask them to vote a certain way. Leave your contact information, and if you have it, relevant articles or examples of similar legislation in other states. Follow up in a few weeks, and if you’ve stumbled upon new information after your meeting, forward it along.

TESTIFY IN COMMITTEE

Both the Ohio House and Senate offer interested parties the opportunity to testify on bills under consideration. This call for public testimony gives advocates and activists an opportunity to speak directly to the lawmakers who ultimately must vote whether a proposal will advance. Short of meeting with each committee member individually, testifying on a bill is the most effective way to influence the people who will be deciding whether to advance a piece of legislation.

If you attend a committee hearing, typically the only witnesses offering testimony are lobbyists and business groups. The opportunity to testify is, ironically, very infrequently used by members of the general public who are most impacted by legislation, thanks to confusing procedures and hard-to-find information. That’s exactly why we’re offering this guide. If you, and other like-minded citizens, take advantage of this process, we guarantee it will get noticed.

To testify on a bill:

- Notify the office of the Chair of the committee at least 24 hours in advance. To find out when committee hearings are scheduled for your bill, see chapter 5.

- Provide them with an electronic copy of your written testimony and a completed “witness slip.” (You don’t have to read your written testimony word for word. You can provide additional details in your written testimony and only present the most compelling parts.)

- Contact the office of the committee chair, or read the instructions provided in the emailed committee meeting notice (see Chapter 3 for how to track legislation via committee notices) for exact requirements.

- In addition to following rules of the committee about testifying, if your Senator or Representative is on the committee in question, call and let them know that you’ll be coming.

It is customary to start testimony by addressing the Chair and Ranking Member (essentially the designated leader of the minority party members – you’ll find their names on the committee pages on the House and Senate websites) of the committee:

“Chairman Smith and Ranking Member Jones, thank you for the opportunity to testify today on House Bill 1. My name is Joe Johnson, and…”

Sorry for the cliffhanger, but you’ll have to take it from there. Say something about who you are, why you’re interested in the legislation and then tell a story or anecdote about yourself, someone you know, your community or your area of expertise.

While you can include additional information in your written submission to influence how a lawmaker thinks about a bill, make sure that the portion of your testimony you read in committee can be read in about three minutes. That’s because sometimes, when there are a lot of witnesses, the Chair will limit the time each person can speak.

If you cannot attend committee, you can still submit “written only” testimony which is distributed to committee members, posted online, and becomes part of the committee record. While it’s not as impactful as being there in person, it’s certainly more effective than an email and counts towards the balance of those in support or opposed.

AT THE HEARING

When you arrive, you can check in with the committee Chair’s staffer to make sure you’re on the witness list, but if you spoke to them on the phone or received an email to confirm they received your written testimony prior to the hearing, you can skip this step. You often won’t know when you’ll be called to testify, so be prepared to wait, sometimes for hours, while other bills and witnesses are called.

When they get to your bill and your name is called, walk up to the podium and start reading your testimony. Testimony is typically delivered while standing, but if you have physical limitations requiring you to sit, let committee staff know that in advance so they can set up a table and chair. Take a deep breath, try to be relaxed and not nervous or you may read too quickly. Members will have a copy of your electronic testimony on an iPad and might be reading along, so don’t worry if they’re looking down.

When you’re done, the Chair will ask if members have questions for you. If they don’t, they’ll thank you for your time and you’re done. Congratulations! If there are questions, it is customary to respond to the person asking the question through the chair, which seems weird, but here’s how it works in practice:

Representative Jones asks you a question;

You answer: “Chairman Smith, to Representative Jones, the answer is____.”

Don’t worry if you forget, just be polite and respectful even if the question is totally dumb. If you don’t understand what they’re asking, restate what you think they are asking, or ask the questioner (through the Chair) to rephrase it. If you don’t know the answer, that’s OK! You’re not expected to be an expert on anything other than your own experience. Feel free to remind them of that. But, if you have more information at home or are willing to do the research, you can offer in your response to follow up with more information after the hearing.

At the end, if there are no questions, you’re done. Good work, citizen!

You can also wield influence by:

USING THE MEDIA

State lawmakers are very sensitive to how they are perceived in their home district. Speaking to them through the media has the dual benefit of alerting other constituents about an important matter being debated at the Statehouse and also to shame and or influence the lawmaker themselves. Most smaller newspapers accept letters to the editor, as long as the author is local and follows basic guidelines for length.

Many papers, including big city outlets, run opinion editorials (op-eds) by subject-matter experts or people speaking on behalf of a larger organization. In addition to shaping public opinion, receiving enough letters from readers can also alert the editorial board of a newspaper that they should weigh in on their own editorial page, ideally in the Sunday edition.

If your group has become frustrated by the response (or lack thereof) from a local lawmaker to an issue that could impact your community, try pitching the story to a local reporter who covers local politics.

USING INFLUENCERS

Enlisting long-standing neighborhood groups (civic groups, churches, nonprofits, chambers of commerce, etc.) can be extremely effective in influencing how legislators think about a particular issue and its impact back home in their district. Check out a legislator’s biography for local groups they may belong to. If you have a connection (you go to the same church or have a mutual friend), use it. Convincing these groups and their leaders to communicate to legislators can be powerful.

AMPLIFYING YOUR MESSAGE BY ENLISTING OTHERS

Power in numbers when the message is delivered in a clear and concise manner can be extremely effective. A large group of constituents will definitely make a member pay attention and think about decisions they make in Columbus. Get your book club, group or organization to make coordinated calls over the course of a day or a week. Enlist your friends to fire off a quick email to their lawmaker. When you get an in-person meeting, take two or three other people with you. Indicate you represent many more. If you testify in committee, encourage others to do so on the same day. As much as possible, make it seem like a groundswell.

INVITING LAWMAKERS TO EVENTS

State legislators love to be recognized in public. And what better way to be recognized than show up at events where you are an invited special guest? Invite your lawmaker to an event in their district where there will be a large number of people they can mingle with—for example, a fancy banquet for an important cause they believe in. You and your group will get some face time, and the lawmaker will start to associate you with a cause or organization in their community.

If your organization has the budget for it, you can actually hold an event – maybe a luncheon or reception – at the Statehouse. Planning the event on a day when the General Assembly is in Columbus, makes it much more likely that multiple lawmakers will be able to attend.

Chapter 3

What goes on at the Statehouse

The Ohio House is made up 99 Representatives and the Senate of 33 Senators. Ohio has legislative term limits, so House members can only serve four consecutive two-year terms, while Senators can serve only two four-year terms before becoming ineligible. Hopping between one chamber and the other is routine. A member may serve four terms in the House, only to run for State Senate where they serve eight more years, then return with a run for the House. Welcome to the carousel! And yes, it’s perfectly legal.

The House and Senate set their own schedule within the two year General Assembly from January to June, before taking most of the summer off. In odd-numbered years, they may return for a few months between September and December. In even-numbered election years, they don’t return full-time until after November elections, when they typically race to pass a flurry of bills during what’s known as the the “lame duck” session just before the two-year legislative General Assembly comes to a close.

OHIO HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

Representatives serve two-year terms and are up for election every even numbered year. The majority party elects six leaders from its members, the chief among them is the Speaker of the House. The minority elects four leaders, with the Minority Leader heading up the caucus.

Senators serve four-year terms. Elections for Senate are staggered such that half the seats in the chamber are up for reelection in each even-numbered year. Odd numbered district Senators run for election at the same time as the governor, while even numbered district Senators at the same time as the presidential election. The majority and minority each have four leaders, with the head of the majority caucus serving as President of the Senate, while the other side elects a Minority Leader.

You’ll notice that there are exactly three times as many House seats (99) as Senate seats (33). That is because each Senate district in Ohio is made up of three House districts.

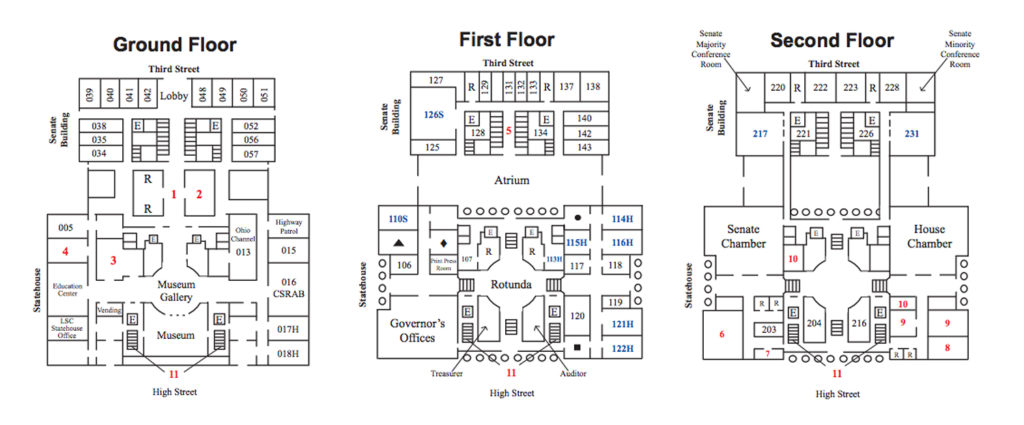

CAPITOL SQUARE

“Capitol Square” is how locals refer to the group of state buildings located near the intersection of High and Broad Streets in downtown Columbus. The Statehouse complex takes up a full city block between Broad, State, High and Third Streets. The chambers where the full House and Senate meet, as well as a museum, restaurant and gift shop are all located within the Statehouse, which faces High Street. The Senate building faces Third Street, and connects to the Statehouse via a two-story atrium area in the center, just behind the iconic rotunda that gives the building its recognizable appearance.

The Senate building is home to the offices of individual Senators and several hearing rooms where committees do their work. House members have their offices on the 10th-14th floors of the Riffe Center, located across the street from the Statehouse at 77 S. High Street. House hearings are held in meeting rooms on multiple levels of the Statehouse, primarily on the south end of the building nearest the House chamber.

The main gathering areas of the Statehouse include the cafeteria, rotunda and atrium. Often, advocacy organizations rent these spaces to host luncheons and events with legislators to promote their causes and build relationships. These areas are also great places to run into—and speak with—legislators and their staff.

There are three levels of parking under both the Statehouse and the Riffe Center, but on session days, the garage can fill up quickly. Alternative parking can be found in the underground lot at Columbus Commons, access from 3rd Street, between Town and Rich, a block to the south of the Statehouse.

The uppermost level of the Statehouse garage connects to the Statehouse via a sliding glass door to the east, and underground tunnels to the Riffe Center (west) and the Rhodes State Office Tower (north).

Thanks to a recent change in security procedures, it’s not easy to find a working entrance to the Statehouse. The doors at the top of those big steps facing High Street? Locked. The only public entrances that are regularly open are the underground entrance from the top level of the Statehouse garage, and the 3rd Street entrance to the Senate building. During business hours, the South Statehouse entrance up the stairs off of State Street is also open. All three require a bag check by the Highway Patrol and going through a metal detector. Security in the Riffe is slightly different: there are no scanners, visitors need to sign in and show identification to be given a visitor pass.

THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS

The work of the Ohio Legislature is primarily to consider changes to the Ohio law, also known as the Ohio Revised Code. You can find a copy of the code online at codes.ohio.gov/orc.

HOW TO READ THE REVISED CODE

The Ohio Revised Code is broken down by titles on different subject matters. The title is listed first as single or double digit number 1-63, then the chapter number, then the section number after a period. For example, a liquor statute about liquor control laws would be 4301.01. Footnotes indicate when the section was originally passed, and when the statute was amended and by which piece of legislation.

How to change Ohio law

When a lawmaker – usually at the urging of an advocacy organization or other interested party – sees a need for a change in Ohio law, the process of enacting such a change is introduced in the form of a bill. In order to become law, a bill must go through a number of steps up to and including being signed by the Governor.

The first step is getting a bill drafted with help from the nonpartisan Legislative Services Commission. Members will often send out a letter to colleagues (of their own or both parties), describing the bill and seeking cosponsors.

After a short period, the bills then get introduced (delivered to the Clerk’s office where it gets assigned a bill number). The bill introduction is read in the chamber it was introduced and gets referred to a committee for hearings to begin. (Find a list of House and Senate committees on the respective chamber’s website).

READING A BILL

At the beginning of a bill, you’ll find the bill number, sponsor, title and short description, followed by a list of code sections that it modifies or deletes. Modified sections are listed in their entirety in numerical order, and text that is underlined or stricken out indicate what is being added or removed.

Bills are numbered according to when they are introduced, and referred to according to their chamber of origin. For example “House Bill 1” is the first bill introduced in the House in a given two-year term of the legislature, also known as a General Assembly. For reference, we are now in the 132nd General Assembly.

BILL INTRODUCTION

Bills are formally “introduced” when they are added into the formal record of a House or Senate Session. If a bill’s status (we’ll get to that shortly) is listed as “introduced,” that means it has not yet been assigned to a committee. If you hate the bill, that’s good news, you can keep an eye on it but can hold off on firing up the outrage machine. If you support a bill and it’s not been assigned to a committee, that’s bad and your best point of pressure is to call the Rules and Reference Committee Chair, who also happens to be the Speaker in the House or the President in the Senate.

COMMITTEE HEARINGS

Once a bill is assigned to committee, the Chair calls the shots regarding how quickly it moves—if it moves at all—through the process. If a bill you care about has the status of being “assigned to committee,” but no hearings have been held, it’s likely not a priority of the committee leadership. If a bill you like is assigned to a committee, get it moving by calling the Chair and Ranking Member on the committee and asking them to hold hearings. If that doesn’t work, exert outside pressure (we’ll talk about that more later). Committees hold multiple hearings on bills before voting to report them out to advance to the Floor. Once “reported by committee,” it’s up to the Rules Committee to decide when or if it will get a vote on either the House or Senate Floor. This is important because if a bill is not immediately scheduled for a vote after referral out of committee, that is a good window for advocacy for or against it.

ON THE FLOOR

To see what’s on the Floor, check the Session Calendar, posted on the Ohio House or Senate website, the day of the vote. On the Floor, members hold debate, offer amendments and ultimately vote whether to pass the measure. If passed, it goes to the other chamber, where the exact same process repeats itself. Lots of bills pass one chamber only to die in the other.

TO THE GOVERNOR

If the Senate takes up a bill that’s already passed the House, or vice versa, it may have made significant changes to it. When that happens, the bill goes back to the chamber of origin, which must hold a vote of all the members whether to accept (or “concur with”) those changes. If they concur, the bill becomes what’s now known as an “Act,” and is delivered to the Governor. If the chamber of origin does not agree with the amendments, a Conference Committee is appointed to work out differences. The Conference report they produce must, in turn, be voted on again by both chambers in order to go to the Governor.

The Governor has 10 days (not counting Sundays) in which to sign or veto a bill or it automatically becomes law.

Committee hearings

When a bill is heard in committee, that’s the time to make your push for or against. There may not be time once a bill leaves committee before it is scheduled for the Floor. Use the tools we mentioned earlier to have influence.

At a hearing, members assigned to that committee will hear from bill sponsors or members of the public on their perspectives on the legislation. There may be multiple bills pending before the committee, and it’s up to the Chair to decide the order in which they are heard. You might need to wait through several other bills before yours is called.

Observers and witnesses can sit anywhere in the viewing area or stand along the back or side walls. Signs, displays and outbursts are not permitted and could result in your removal. If you want committee members to notice the presence of your group, instead of signs, try wearing matching t-shirts or buttons. Recording video is not allowed without advance permission of the Chair. Rules about photography vary by committee. In general, don’t be obvious in taking pictures. Hearing rooms have free WiFi provided by the Ohio General Assembly and live tweeting the proceedings is a great idea, but make sure your phone or laptop is fully charged.

The first hearing of a bill in committee is limited to testimony from the lawmaker or lawmakers who sponsored the bill. In their remarks, they will explain the intent of the legislation and answer questions from members of the committee. Normally no other testimony will be heard.

A second hearing can come as soon as the next meeting of that committee (if the bill is a high priority for leadership), or may never occur (if it’s a low priority). At the second hearing, the normal practice is for supporters or “proponents” of the bill to testify. Opponents usually have an opportunity to make their case against a bill at its third hearing. Obviously if there is a lot of interest, sometimes bills can extend these opportunities and schedule fourth or fifth or even more hearings, giving all interested parties a chance to weigh in.

Once the committee is ready to advance a measure to the full House or Senate for a Floor vote, it will announce on an upcoming hearing notice that a vote is possible. If it passes, it’s said to be “reported” by the committee, at which time it’s up to the Rules Committee to decide when to schedule it for a vote on the Floor.

A note about votes: only a small fraction of the bills heard by a committee will actually receive a committee vote. Votes in committee are scheduled at the discretion of the Chair, who consults with the leadership of his or her party – always the majority party in control of the chamber – whether to advance a measure, based on whether they believe it has the votes to pass. That means if you see a bill scheduled for a possible vote in committee, if it’s something you oppose, it’s time to pull out all the stops and unleash opposition. Bills scheduled for committee votes have been known to be pulled from the calendar when leadership gets nervous based on a backlash in the days leading up to a hearing.

A weekly schedule of upcoming committee hearings is typically posted on their website on Fridays by the House and Senate. Most committees meet during the day (and a limited few at night) on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, with a few meeting on Thursday mornings. Most committee hearings are not televised except for the Finance Committees that work on the state budget, as well as a few other select committees in the Senate. If available, hearings are televised on the Ohio Channel and online at http://www.ohiochannel.org. However, for the most part, if you want to watch a committee meeting, you’ll need to be at the Statehouse when it meets.

More on Session

The legislature typically meets Tuesday, Wednesday and occasionally on Thursday. Session is televised on the Ohio Channel and on their websites. Calendars for session are put out in January for January-July and July for July-December. Session gets cancelled regularly especially in early and late months of the calendar. Always check the House and Senate websites for updates. The calendar for the day is posted both online and posted outside the respective chamber. Bills listed above the black line typically will be heard that day. When session starts, there’s a prayer, the Pledge and a variety of other business before bills for 3rd consideration (up for a vote) are heard. Other members are then allowed to ask questions about the bill or express their support or opposition for the bill.

House session: Audience members must sit in the balcony and are not permitted on the Floor. Lobbyists congregate outside the chamber which is also a good place to interact with members. Members’ votes in the House are almost instantaneous and displayed on a big board on each side of the chamber. Each member has buttons on their desk that they press. A member’s name lights up green if they vote for a bill and red if they vote against it. A tally is then displayed on the board.

Senate session: The Senate is a bit more intimate. The audience and lobbyists sit on the same level as members on benches to the side behind railings. Votes are done by a roll call vote with a member verbalizing their support or opposition to a bill.

Both chambers have Sergeant-of-arms who enforce the rules of each chamber. Signs and demonstrations are not allowed. If you are unhappy with the outcome of a vote and respond with some form of disruption (banners, signs, shouts, songs, chants or other outbursts), you will be escorted out. Shooting video (or obvious photography) is prohibited without first getting consent from the Clerk.

Votes and vetoes

Most bills that are discussed on the Floor are typically passed. It is extremely rare for a bill to be discussed on the Floor and not pass. Once the bill passes both chambers, it goes to the Governor for their signature/approval or veto. Vetoes can be overridden by the chambers if 3/5 of the members vote to override the Governor’s veto.

REFERENDUM/BALLOT INITIATIVES

There is a way to get a law passed or amend the Constitution without the legislature. There is even a way to get do a “citizens’ veto” of a bill that was recently enacted into law. For such ballot initiatives and referendums, signatures must be gathered from at least 44 of Ohio’s 88 counties. Petitioners must gather signatures equal to a minimum of half the total required percentage of the gubernatorial vote in each of the 44 counties: 5 percent for amendments, 1.5 percent for statutes, and 3 percent for referendums.

THE STATE BUDGET

At the beginning of odd numbered years the governor releases his state budget proposal which is then introduced as a House bill. The budget not only addresses state spending, but many policy issues as well (policy changes technically must be germane to the budget, but that is loosely interpreted). Because it’s a “must pass” bill (meaning that it has to be passed by July 1 which is the beginning of a new fiscal year), many things get put in the budget (some hastily and quietly at the very end) and move rather quickly. If you want to know more than you’ll ever need to know about the state budget process, visit http://www.lsc.ohio.gov/guidebook/chapter8.pdf.

To find out what is in the budget, go to LSC’s budget website at lsc.ohio.gov. The most practical resources on the budget are available from the LSC front page, via the second link in center of page, called “Budget bills and related documents.” The first tab on the budget page leads to the “main operating” budget, which links to the “Comparison Document” and “Bill Analysis” which are the two most useful tools to follow the budget.

The Office of Budget and Management also maintains a budget front page at www.budget.ohio.gov with information from the Executive laying out their budget proposals.

To find out what is in the budget go to LSC’s budget website at lsc.ohio.gov.

Chapter 4

Working with the Executive Branch

While the executive branch consists of six statewide elected officials (Governor, Lt. Governor, Attorney General, Secretary of State, Treasurer and Auditor), for purposes of this guide, we’ll focus on the Governor and the cabinet agencies. (Note that the Ohio Department of Education is not run by a gubernatorial appointee, but instead governed by the State Board of Education.) Ohio’s Governor and other statewide elected officers can serve two consecutive terms of four years each.

While the legislature is the branch of government that collectively introduces and votes on bills, in the end the Governor singularly decides if a bill becomes a law or not with the stroke of a pen.

But the Governor cannot introduce bills, so calling the Governor’s office alone to influence the legislative process is rarely effective, unless a bill has passed both chambers and is headed to the Governor’s desk. Then you can call to request (or oppose) a veto. The same rules apply about amplifying your message by organizing other people to call as well.

The relationship between the legislature and the executive branch is typically a love/hate relationship, even when they are controlled by the same party. Sometimes they team up on issues and other times they are diametrically opposed. The Governor and his cabinet even have staff whose sole responsibility is lobbying the legislature to advance bills the Governor supports or stop bills the Governor doesn’t want to show up on his or her desk.

Contacting the Governor’s Office

Calling the Governor’s office or meeting with staff can be meaningful if you want him/her to support or oppose (and eventually veto) legislation. To weigh in this way, try to contact the appropriate member of Governor’s office staff (usually one of the people with “policy” in their title) rather than calling the main number or going through the constituent hotline. A public copy of the staff list can be found at http://www.gongwer-oh.com/public/govstaff.pdf.

If you have a problem with a state agency, calls and meetings with the Governor’s staff are good ways to apply pressure. State agencies serve stakeholders and the last thing an agency wants is to get a call from the Governor’s office (their boss) that a stakeholder or a large group of citizens is unhappy.

When dealing with the executive branch, the same rules apply as dealing with legislators – make a specific, actionable request and follow up. And again, there is strength in numbers.

EXECUTIVE ORDERS

Just like the President of the United States, Ohio’s Governor can sign executive orders (EOs) using authority already granted to him in Ohio’s Constitution or ORC. However, because of Ohio’s legislative checks on the executive branch (see below), they tend to be not as sweeping as federal level EOs. Some EOs are ceremonial, some are technical, but some do have important policy implications, so keep an eye on them.

LEGISLATIVE OVERSIGHT

Two of the most unknown yet powerful entities in the state are JCARR (Joint Committee on Agency Rule Review) and the Controlling Board. These are legislative oversight agencies on the executive branch.

JCARR is a legislative committee that reviews rules and regulations that agencies set outside of the Revised Code and are set in the Administrative Code – some of which can be very significant. The public comment period on rules is a good opportunity to have influence, especially for agencies that have a lot of discretion like Medicaid, JFS, Health, Commerce, etc. Getting traction at JCARR can be easier if there is a big to-do at the public hearing and many comments filed on the rules.

JCARR meets once or twice each month, usually on Mondays, and the website offers a tool to be alerted when rules on certain topics are up for review.

The Controlling Board is where the money is. Agency budgets are set every two years in the biennial budget process, so if an agency wants to increase its spending authority, or enter into a contract with a vendor that exceeds $50,000, the Controlling Board must approve. Meetings occur every other week on Mondays and the agendas are available online in advance.

Chapter 5

Learn more about legislation

If you’ve heard about a bill but have no idea how to influence its passage or defeat, the first step is finding out what it does and where it is in the process. To do that, you’ll need to get on the legislature’s website: http://legislature.ohio.gov.

LEGISLATION SEARCH

Search for legislation on legislature.ohio.gov

- Search by bill number or, if you don’t know it, by the name of the sponsor. The keyword search is next to useless.

- If you can’t find the bill number, call the sponsor’s office and ask them for the bill number. They’ll be happy to know someone’s interested. They might be willing to send you an electronic copy of the bill or provide a copy of their sponsor testimony if you ask them.

By the way, if a bill you oppose hasn’t been introduced yet, celebrate! You can focus on something else for a while. If a bill you support hasn’t yet been introduced, call the lawmaker you think might be interested in your issue and ask for a meeting. Talk to them about why the issue is important. They might be willing to get legislation introduced.

VIEWING A BILL ONLINE

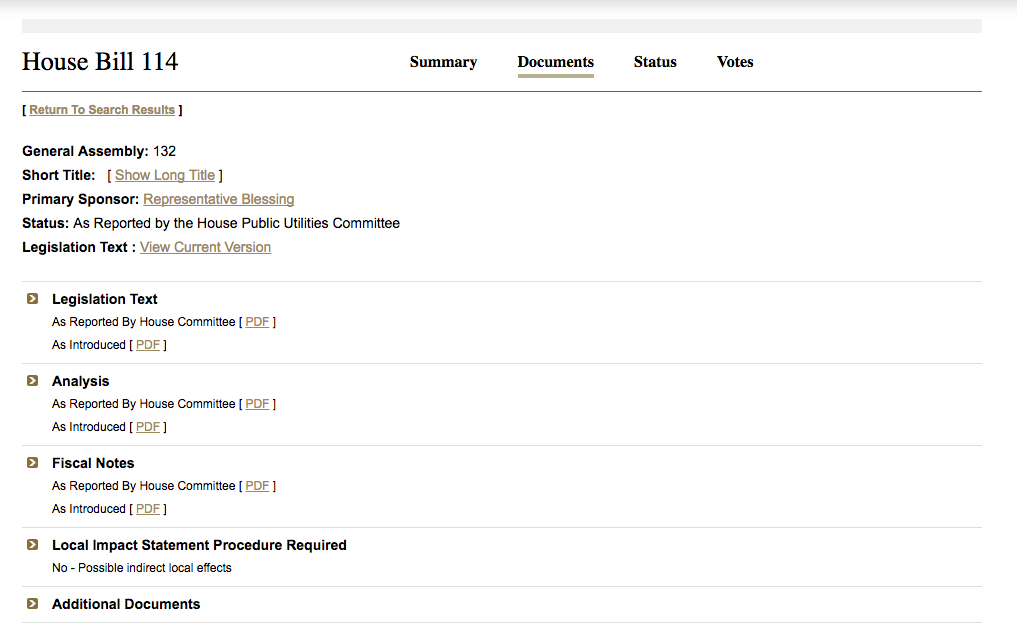

Here you can see the bill’s title, sponsor, cosponsors, status, bill text and the committee it’s been assigned to.

To learn more about what the bill does, view the “Documents” page:

Here you’ll find the legislation, including changes that have been made to it throughout the process. For example, if a bill has been amended, the original “as introduced” version of the bill will be listed alongside the more recent versions.

HOW TO READ A BILL

Bills will have different versions as they go through the process. The version is identified at the very top, followed by the bill number and other details and the names of is primary sponsors and cosponsors. The following block of text features a brief description of what the bill actually does, including what sections the bill is amending or creating.

Section 1 of the bill describes which section will be amended or enacted by the language of the bill, which follows with each modified section of code shown in its entirety, organized in numerical order. Language that is not underlined is law already contained in the Revised Code. Underlined text is new language to be added to the code, while language stricken is to be removed. A bill that creates a completely new section will contain all underlined language and an amended law will contain both.

If a bill has had at least one hearing, the Documents tab will also be a copy of the bill analysis—a plain English summary of what the bill does. A fiscal note is required in time for a bill’s second hearing and provides an estimate of the financial impact of the bill to the state and local governments. It’s important to note that, if a bill has a financial impact on other entities – businesses, individuals or other parties, it’s not part of the fiscal analysis.

CHECKING A BILL’S STATUS

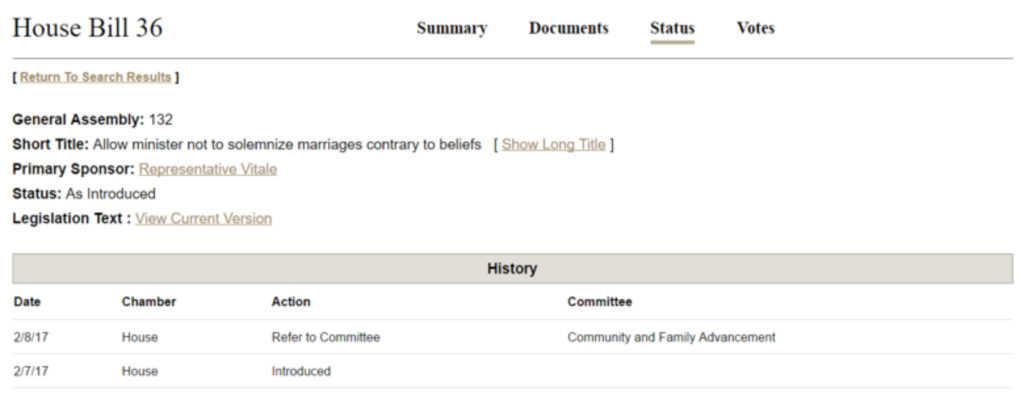

If, upon review of the bill and bill analysis, you are still concerned about the legislation, you’ll want to know where it is in the process. To do that, check the bill’s status page:

In this example, you see the most recent update is the bill went to the Community and Family Advancement committee. So, at this stage, you’ll want to follow it through the committee process.

TRACK LEGISLATION

Unlike Congress, the Ohio legislature provides no helpful bill tracking tools. There are subscription services which cost a fortune, but to do it yourself, here are some suggestions:

Track a bill in committee – two options:

- Sign up for committee notices by contacting the chair of the committee (to look up the committee or chair, click on the committee name from the bill summary page)Every week, on late Thursday or Friday, you’ll get notice of any hearings scheduled for the following week and will get early notice if your bill is moving.Also from the committee website, you can see a calendar of past and future hearings and download copies of testimony from other witnesses.

- Check the weekly committee schedule on the House or Senate website.

If you see your bill listed on a committee notice, you’ll see if they’re taking testimony and/or holding a vote. From here, you have some options:

- If you’d like to testify, wait for a notice they are taking proponent or opponent testimony, depending on your position and follow the instructions on the notice to submit your testimony in advance.

- If your bill is flagged for a possible vote, contact your member if they are on the committee and remind them how you’d like them to vote.

- To find out how the committee members voted, check back after the hearing – if the status indicates it was passed (or “reported”) by the committee, use the “votes” tab for the roll call.

Once a bill is out of committee:

- Watch the calendars for upcoming House or Senate sessions (on the House or Senate website) to see if it’s scheduled for a vote. Or, to get alerts via email, sign up with the Clerk’s office for email notifications of Rules Committee activities. Read the regular “Rules report” to see which bills have been scheduled for Floor votes.

- Once you see your bill, it’s showtime. Start making phone calls if you want your lawmaker to know how you expect them to vote.

Online Resources

To stay up-to-date, sign up for our daily news, legislative alerts and issue-specific updates at innovationohio.org/signup.

GET UPDATES FROM INNOVATION OHIOFor Email Marketing you can trust.

Here are some other sources we reference in the guide.

Statehouse Resistance Manual This guide, future editions and supplementary materials can be found here: www.ohioresistanceguide.com

Ohio Legislature (Legislation Search): www.legislature.ohio.gov

Ohio Senate: www.ohiosenate.gov

Visit for Session Calendars, Session Journals, Majority & Minority blogs, etc.,

- Member Directory: ohiosenate.gov/members/senate-directory

- Committee Schedule: ohiosenate.gov/Assets/CommitteeSchedule/calendar.pdf

Ohio House: www.ohiohouse.gov

Visit for Session Calendars, Session Journals, Majority & Minority blogs, etc.

- Member Directory: www.ohiohouse.gov/members/member-directory

- Committee Schedule: www.ohiohouse.gov/Assets/CommitteeSchedule/calendar.pdf

Legislative Services Commission (bill analysis and technical assistance): www.lsc.ohio.gov

Ohio Budget Process: www.lsc.ohio.gov/guidebook/chapter8.pdf

Guidebook for Lawmakers (A deep dive version of the sections above on how the process works): www.lsc.ohio.gov/guidebook/

Controlling Board of Ohio (legislative oversight, fiscal): ecb.ohio.gov

Joint Committee on Agency Rule Review (legislative oversight, policy): www.jcarr.state.oh.us

Ohio Revised Code (current laws of Ohio): codes.ohio.gov/orc

Ballot Initiatives and Referendum Process: www.ohioattorneygeneral.gov/Legal/Ballot-Initiatives

Governor’s Office: www.governor.ohio.gov

Cabinet Agencies: www.governor.ohio.gov/Administration/Cabinet.aspx

State Board of Education: education.ohio.gov/State-Board

Ohio Statehouse (event reservations, parking info): www.ohiostatehouse.org/

The Ohio Channel (House and Senate broadcasts): www.ohiochannel.org

Office of Budget and Management: www.budget.ohio.gov

Materials on the Governor’s “As Introduced” budget submission.