What you need to know about Ohio Politics and Policy

Stephen Dyer · March 22, 2013

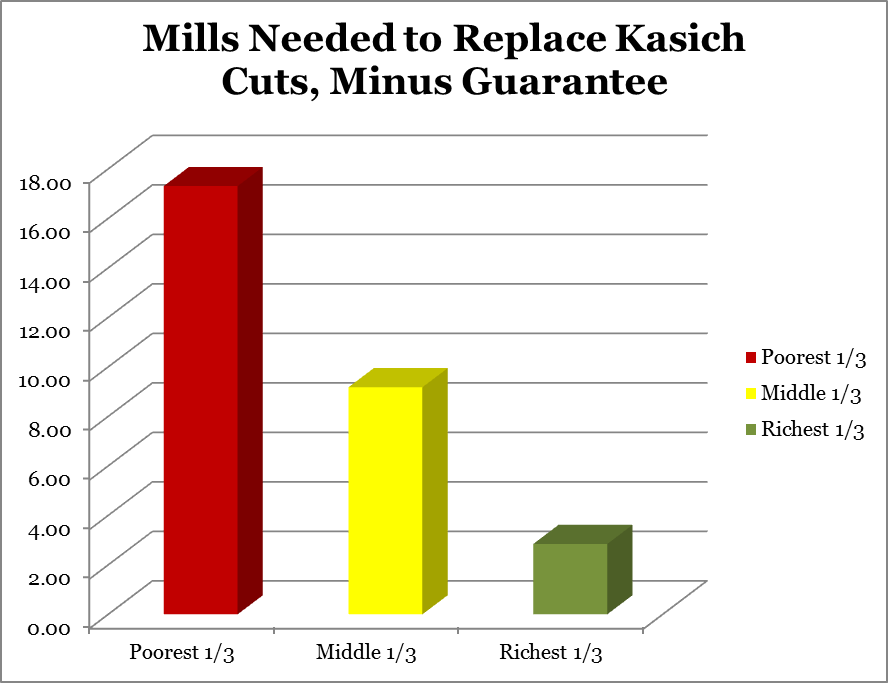

Why poor districts dislike the Kasich school plan

When more than 100 Ohio School Superintendents showed up in Columbus last week to voice their displeasure at Gov. John Kasich’s education funding plan, many wondered, “Why?” There have been many school funding initiatives since the DeRolph school funding lawsuit was first filed in 1991. Yet such a showing hadn’t been seen in Columbus since that case was in full bloom. Kasich’s plan increases money to districts compared to his previous budget primarily through two temporary funding streams: a $300 million innovation fund and about $880 million in the form of a guarantee that ensures no district receives less revenue than they did in this school year. Unfortunately, there are two problems with the guarantee: 1) The amount it’s based on — this school year — represents a huge cut from when Kasich entered office, and 2) Kasich promised to eliminate the guarantee in what some superintendents are assuming could be as soon as two years. Superintendents certainly aren’t counting on it for their five-year forecasts. So what happens when the guarantee goes away? Here is a graphic that helps explain why School Superintendents, especially in property poor districts, are so exercised about Kasich’s plan. After the guarantee goes away, Ohio’s property poorest districts have to come up with, on average, 17.3 mills to replace the state funding cuts. That’s more than two more mills than Cleveland passed last November in one of the largest levy asks in recent memory. There is simply no way, for example, that folks in Perry County’s Southern Local will pass nearly 60 mills in local property taxes, just to keep pace with revenues from 3 years ago. What the elimination of the guarantee means in reality is massive cuts. How massive? Try cuts on the order of closing High Schools. That as much as anything helps explain why more than 100 Ohio School Superintendents showed up in Columbus last week for the first time in three decades.Tagged in these Policy Areas: K-12 Education | Ohio State Budget