What you need to know about Ohio Politics and Policy

Stephen Dyer · August 21, 2013

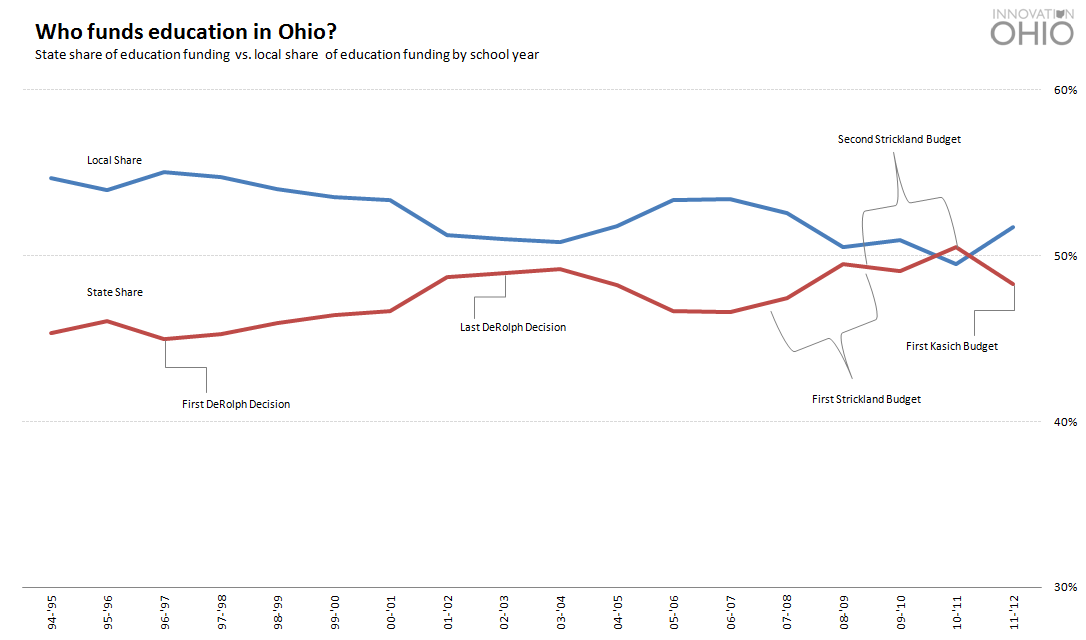

State share of education spending reverses positive trend

In 1991, Perry County high school student Nathan DeRolph filed a lawsuit against the State of Ohio for failing to provide him and every child in the state a “thorough and efficient” system of public common schools. Six years later, in a landmark Ohio Supreme Court case, the Court ruled that DeRolph was right; the way Ohio funded its schools ran afoul of the Ohio Constitution. The central bone of contention in the case was the “overreliance” on property taxes to pay for schools. Relying on property taxes, which produce extremely different amounts of money based on a community’s wealth, further accentuates existing inequities across communities, the Court reasoned. So the Court ordered the state legislature to beef up the state support to its public schools enough so that districts would not have to rely as much on property taxes to pay for its operations. After three more rulings asserting that the state had failed to do that, the Ohio Supreme Court decided to drop the case in 2002. Here’s what happened:

Tagged in these Policy Areas: K-12 Education